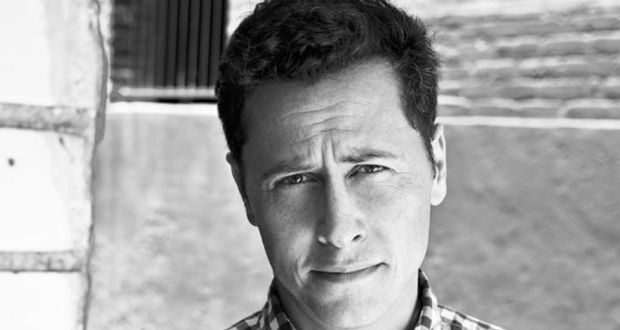

En Veilleuse: An Interview with Matt Sumell

Matt Sumell’s debut novel, En veilleuse (Making Nice) follows the tribulations of Alby—a thirty-something struggling to find his foothold in life amid many failed, although constantly renewed, efforts to pull himself up. The book opens with the death of Alby’s mother, and closes with him tricking his father into coming to her grave. Ferociously funny at times, surprisingly tender at others, En Veilleuse is a crude and honest narrative of Alby trying his best to cope with grief.

Ever since his childhood in Oakdale (Long Island), Alby’s hypersensitivity – and total inability to control his emotions – has earned him a long string of fights and trouble. As Sumell likes to say, “bad choices make for good stories”; and thanks to the remarkable profusion of Alby’s poor decisions, En veilleuse is filled with great ones!

Shortly after getting into college, Alby drops out and starts a series of odd jobs, kicking off his tumble down the social ladder. Needless to say that with girls, things are not looking good either. Alby is better at systematic deception than commitment. Nevertheless, our protagonist finds some comfort in the deep connections he has with animals and the close members of his family. Perhaps because they are the only ones who provide him with unconditional love.

One of Sumell’s great strenghs is the stunning immediacy of his writing. Not that many authors can make you feel, from the very first line on, such empathy for their characters. With a masterful touch — and a sharp sense of humor —, Sumell conveys the absurd and mundane experience of life against a background of rage, insecurity, and infinite sadness. En veilleuse is one of the delights of this Spring. It delivers a rare pleasure, quite similar to a friend confiding an essential and intimate experience —one that makes you feel less alone. Once I finished reading it, I had a hard time letting go of Alby. So I wrote to Sumell, and he was kind enough to chat a bit about the books he admires, those he dreads, his art, and, you know, life!

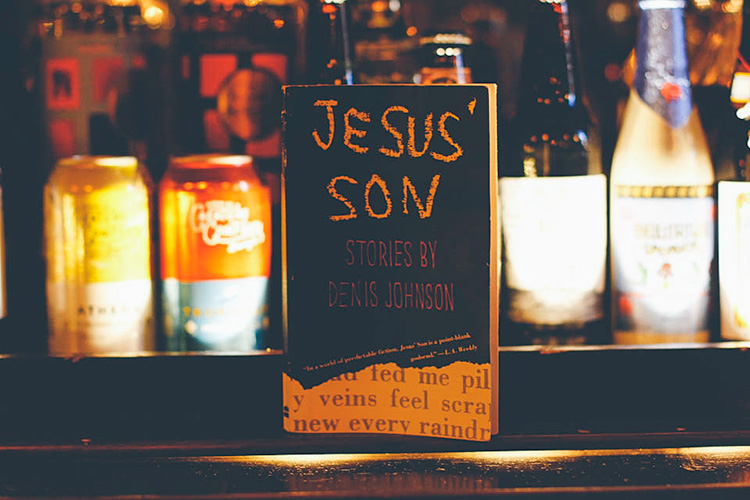

MB: When asked about which books have had an influence on the way you read, you often mention Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son. Could you explain how that book changed your views on literature?

\

MS: I was incredibly under-read at the time I read Jesus’ Son and didn’t know that was possible before, and by that I mean all of it. It surprised me on so many levels—structure, the combination of humor and heartbreak, the spare beauty of his language. I mean, just consider how Johnson describes hearing a boat coming upstream: “The sound curlicued through the riverside saplings like a bee…”

It’s synesthetic: in ten words the guy gives us a visual of noise clumsy-flying like a bumblebee, plus the river, plus the saplings, plus the boat. I imagine this is what a dog feels like chasing a car—no way I can keep up, but I sure like trying anyhow.

I return to it two or three times a year, at least. The book gives me both a sense of permission and something to aim for.

MB: In an interview with the online magazine Boats Against The Current, you raise the point that writers might be less influenced by authors they admire, than by those they strongly dislike. Would you share with us some writers that are not your favorites, but whose work might have informed yours?

MS: I’d hate to be ungenerous to anyone specifically—it’s hard enough out there—but there’s a lot getting published today that I dislike, not because it’s terrible work so much as just ok. Mediocrity is the absolute worst, because it moves us in neither direction. It doesn’t challenge us, it doesn’t teach us, it doesn’t offend or thrill us, it doesn’t do much of anything but pass the time. But even that’s influenced me, in that it’s something I strive to avoid. I’d much rather risk upsetting readers than bore them. I suppose it’s related to my thoughts on “likeability”—of writers playing it safe so as not to upset some idiots looking for things to be upset about. F*** likeability. Be interesting.

But maybe it’d be better to tell you that at sixteen years old I thought Bukowski was the best thing ever.He spoke to the younger me. I bought into the macho, bar-fighting, over-sized sentimentality of a drunk, and I mimicked him. Poorly. And while I can’t call him a favorite anymore, he was still a huge influence. In a way, En Veilleuse is an attempt to dismantle all that macho sh**, to explain it, to get at the elusive, slippery vulnerability behind and beneath it. I needed Bukowski — he opened some doors — but man did I ever need to let go of him too…

MB: In En veilleuse, your style shifts regularly: from dry and tense prose with an ordinary language to lyrical, melancholic, and even almost sentimental writing. A great deal of humor is also present as we see Alby struggling with life in a series of comic/absurd situations. Would you say that you have been influenced by stand-up comedy?

MS: I just think humor is the great saving thing. Without it, I’d be lost in all that despair. I need to laugh to survive, to make light of all that dark, and there’s plenty of dark. So as much as I love and am surely influenced by stand-up, I also think that literature has to be more than that. You have to make them laugh and break their hearts. Otherwise, where is the gravity? Where is the seriousness to the project?

MB: In A l’horizontal and OK the pace calms down, we reach moments of quiet sadness, and the heart of the story seems to hide somewhere under the surface of the narrative.

MS: I think that’s where I settled into things. I quit being really hard on the work as I was writing it and just let the stories suck for a while. I stretched it out a bit. A l’horizontal and OK are the two longest stories in the book, and two of the last that I wrote. I’d say that’s me “maturing” as a writer, but I’m not sure me and mature belong in the same sentence.

MB: Some of your chapters’ titles echoed in my mind with some of Amy Hempel’s work (To The Gate of the Animal Kingdom), and (In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried). Is it intentional? Or is it just another sign of my own obsession with Hempel? MS: I love Hempel—that Al Jolson story in particular–but yeah, no, you’re totally obsessed. I can’t even figure which title of mine sounds like In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried.

MB: What prompts your stories? A sentence? A character? A situation? Do you ever begin writing a story with a piece of dialogue?

MS: I try to avoid opening with dialogue, I think because it seems like people talking in a vacuum. The writer Ron Carlson has this idea: Nothing happens nowhere. We need setting, if only a little. That said, there’s a story in En Veilleuse that does. But I very quickly, in the second sentence, let people know where we’re at.

As for what prompts stories—lame answer, I know—it’s different every time. I suppose most often it’s some interesting personal experience that I’ll use as a springboard into a story and fictionalize from there. Sometimes all the prompting I need is a deadline. Sometimes it’s pure will, a stubbornness that borders on diagnosable. A l’horizontal, for example, took me seven years from start to finish. It was a total slog. I was just mining experiences, day after day, for years, trying to exhaust them of their emotion. I guess I feel like that’s worth mentioning because sometimes it doesn’t come from inspiration. I wasn’t inspired. At all. If anything I was frustrated and pissed off. But writing is like any other job—you’ve got to put your hours in. I once gave the writer Marisa Matarazzo an old-school time clock, with the punch cards. Put your hours in. Whatever the strange thing is that gets me going, though, it takes a little luck and a lot of work to turn it into something worthwhile.

MB: In France during the 1970s, Serge Doubrovsky spearheaded a new literary genre called auto-fiction. This new trend operated as a form of self-examination through fiction, an introspective reflection on one’s relation to selfhood. Would you say that En Veilleuse fits this genre?

MS: First time I’ve heard of it. And while it sounds like En Veilleuse could fit in, as Groucho Marx put it (potentially on the Al Jolson Show back in 1949): “I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member.”

All that to say I’d prefer to be unclassifiable, and outside of that, to leave the classifying to others. I just write the best I can.

Matt Sumell is a graduate of UC Irvine’s MFA Program in Writing, and his short fiction has since appeared in the Paris Review, Esquire, Electric Literature, Noon, McSweeney’s, One Story and elsewhere. He is the author of Making Nice (Henry Holt, 2015), translated into French by Jérôme Schmit, as En veilleuse (Plon, 2016).