“We all need stories to live”: Marilynne Robinson’s translator, Simon Baril, discusses his debut novel

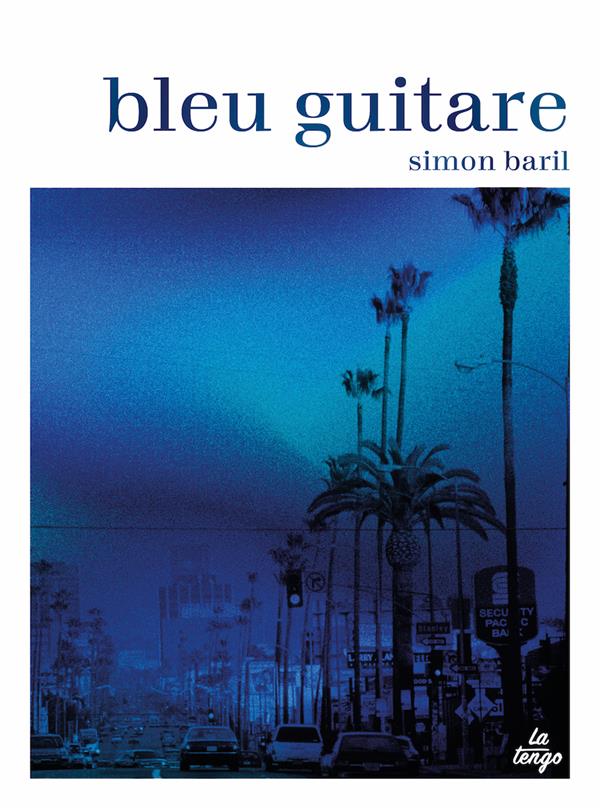

Los Angeles, 1997. A French guitarist is found unconscious, with his hands literally smashed, in a dead end street near the hall where his rock band has just performed. 9 years later, our man has still not recovered, and leads a ghostly existence. How did he become a ghost of himself, tracking the shadows of his past along LA boulevards? According to him, no drug or alcohol should be blamed for his fall, “just emptiness” and the loss of his dream of music and fame.

On most days our unnamed narrator sleeps, and at night he haunts the streets of Redondo Beach and nearby neighborhoods. One day, he starts detailing his life – or lack thereof – in a notepad. Is he hoping to shed light on the events of that fateful night, or more secretly, to get his life back on track?

Readers might be familiar with Simon Baril’s superb translations of Marylinne Robinson’s work in France, as well as many others American novelists. Bleu Guitare, his first foray into fiction, is a spellbinding evocation of a down-and-out Los Angeles. We grew eager to know more, and Simon was kind enough to sit with us. You’ll find the resulting conversation below.

Albertine: First of all, congratulations: we fell head over heels for Bleu Guitare. You have a knack for describing the very peculiar charms of LA, and the emotion that surges from its landscape: its half-empty lots, cheap motels, stucco buildings, fast food joints. All these elements try hard to create the illusion of abundance, but end up hardly concealing the city’s poverty, solitude and vanishing dreams.

Simon Baril: My first memories of Los Angeles date back to when I was eight years old. My parents and I were visiting a beloved aunt who lived in Santa Barbara. The last night of our trip, we stayed in a motel close to LAX. There was a small, uninspiring swimming pool… But it was there, under the roar of all those planes, that I first learned to swim (sports-wise, I wasn’t particularly precocious). Even at the time, even to my young boy’s mind, it felt very special that it happened in LA

I only started really exploring the city when I turned eighteen and left my native Alps to study at UCLA, then intern in a small entertainment agency in West Hollywood. I loved the smells – the exotic plants and even the exhaust fumes, so different from French exhaust fumes! – the balmy air, the shades of the evening sky… Most of all, I loved that I was now living in

the city I had seen in a thousand movies and TV shows, the heart of my fantasy world, the place where dreams come true.

Except of course most people come to LA to have their dreams broken. That’s what I saw all around, that’s kind of what happened to me as well, and it’s certainly what Bleu Guitare is about. But there’s magic and beauty in the way LA does the heart-breaking, at least in my case. I was transformed by this city, and my love for it has only grown ever since. I moved back to France long ago, but I have kept returning over the years, always trying to uncover this place’s secret, or at least breathe its scent one more time.

A: Simon, why did you decide to make your narrator amnesiac? What was made possible thanks to this decision?

SB: The book came out a few days ago, and already a couple of people have used that word in their reviews. It may seem odd, but I had never thought of my narrator in those terms. So it’s definitely not a conscious choice I made.

“Amnesiac?” Sure. There might be other interesting interpretations, but I can’t deny there is something wrong with this man. He suspects as much himself, though what is wrong isn’t exactly clear to him. That’s probably where the novel’s biggest mystery lies.

A: There are many beautiful shifts in your narrative, from night to day, from dreams to consciousness, between present and memories…. Do you have a fondness for the in-between zone? If so, where do you think it comes from?

SB: Thank you for pointing this out. And for forcing me to confront it! In my case, I’m in-between France and America, English and French, dreams and reality, images and words, accustomed to city life but more at peace in the country, in love with solitude but sad when my wife is away… No surprise I spend most of my day translating, an in-between activity par excellence.

Sometimes this in-betweenness feels like a curse, something that pulls me apart. Sometimes it feels like the only way I can sort of be at home in this life, even if I always have to work at maintaining the right balance.

As for my narrator, in general we get the sense that he is trying to move away from a world of night to a world of day. The night world is the safest of the two; but in it he is only half alive, “a zombie,” as he puts it. On the other hand, for him the day is fraught with danger. It’s associated with a certain reality he tries hard to escape.

A: Your narrator seems obsessed with deleting every lead that would allow us to identify the protagonists or key details of the story — name of the band, of the concert hall, series in which a protagonist has played. Why is that?

SB: I think it goes back to this idea of night. Remaining in darkness – protected. Wanting, needing to tell his story without having to reveal too much of himself. But it raises questions, doesn’t it? Such as: Could he have something more ominous to hide, from us and from himself?

A: As I was reading your book, I felt the need to watch the movie adaptations of Chandler’s novels again, and I have found some connections: the whiskey bottle with which your narrator has been assaulted, the elusive woman character, John the neighbor pornographer, the kid who plays in the motel’s yard. Are these voluntary choices or merely coincidences?

SB:: Raymond Chandler is indeed mentioned in Bleu Guitare. The narrator notices The Big Sleep on a library shelf, and is struck by how its title echoes the past nine years of his life. It’s fitting for the master of Los Angeles noir to make an appearance, even though I haven’t read his work or watched a movie adaptation in far too long.

Interestingly enough, the characters and details you mention were all inspired by people I knew, things I saw or heard about. Real people, real things; but they also fully belong to the noir imagination. So now we return to the idea of in-betweenness, specifically the in-betweenness of Los Angeles – perhaps the most in-between city in the world! Every sidewalk,

every street corner: one foot in reality, one foot in dreams/fantasy. David Lynch might be the artist who dramatized it best.

Yet I must point out that while Bleu Guitare is permeated with the LA noir imagination, and solidly grounded in LA’s material reality, it’s also truly a French novel, with a French sensitivity and echoes of French culture. I hope it makes for an engaging mix.

A: I also rewatched Sunset Boulevard and saw more echoes, not with the drama per se, but with the twilight atmosphere, the demise of artistic ambitions, an almost pathological perception of time – an omnipresent past, a ghostly present – a predilection for everything ludicrous?

SB: I remember watching Sunset Boulevard on TV in the 1990s, when I was a teenager. I thought it was the best black and white movie I had ever seen. Since I finished writing Bleu Guitare, I’ve been wanting to watch it again, if only because the actual Sunset Boulevard plays a big role in my novel. I’m a little nervous about it, though. Will I be disappointed? That’s unlikely given its status as an undisputed masterpiece. But maybe it will reopen some old wounds. Wounds that, at the time when I saw it, it seems to have predicted.

A: “Emptiness, nothingness, hollowness” are words that you frequently use to describe the feelings of your hero or the narrative’s atmosphere. I was wondering whether these words could also apply to the condition of the reader who feeds on someone else’s fiction?

SB: At a very basic level, the emptiness my narrator feels is rooted in the fact that, by tragic fate or personal choice, he has been cut off from his family and friends, from the music that he lived for, from everything and everyone dear to him. For almost a decade he has lived a purely material life, a seemingly barren life, walking down the streets of the South Bay at night, feeding, sleeping, and that’s it. It gave him a chance to experience the sheer flesh of Los Angeles, the city without the dreams. In that way LA can feel strangely cardboardish, like an abandoned movie set (here I’m reminded of Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust, another book I want to read again).

You point to a possible deeper level, how my narrator’s story might mirror the general condition of being a reader hypothetically deprived of all her books… The truth is we all need stories to live. Not just as readers, but as human beings. The problem with this man is that his story was brutally interrupted, and for too long he has existed in limbo, unable to either resume his story or start a new one. Bleu Guitare is about a man who is trying to leave a netherworld, a purgatory of sorts. Naturally, it will only happen if he can somehow face and make sense of his past.

A: You are the acclaimed translator of internationally admired US writers, and Bleu Guitare is your debut novel. How was the experience of transitioning from author of a translation to author of fiction? Was it an easy one or was it challenging to be the only person at the helm?

SB: The basic idea for Bleu Guitare came to me in the late 1990s, during my Los Angeles years. That’s when I dreamed up that character, that guitarist with the broken hands. But it took me a long time to find the right way to tell his tale. Only when I decided that it would be a first-person narrative, and that he would write it as he could, with the truth he knew and/or was willing to share, only then did things catch fire. Once I gave him the keys, I was just a translator again, channeling somebody’s else voice. Or so I told myself.

What I learned from this novel is that the frontier between writer and translator is really thin. The story is always out there, whether it’s a book in front of you, first written by somebody else in another language, or something in your subconscious that begs to be brought to light. And whether it’s a translation or an original novel, the hard part is always the same: the rewriting, as Hemingway would say. Over and over again, until things sound as they should, or as close to the way they should as possible.

Bleu Guitare, Simon Baril, editions La Tengo

Click here to purchase this book with us