A Night at The Movies

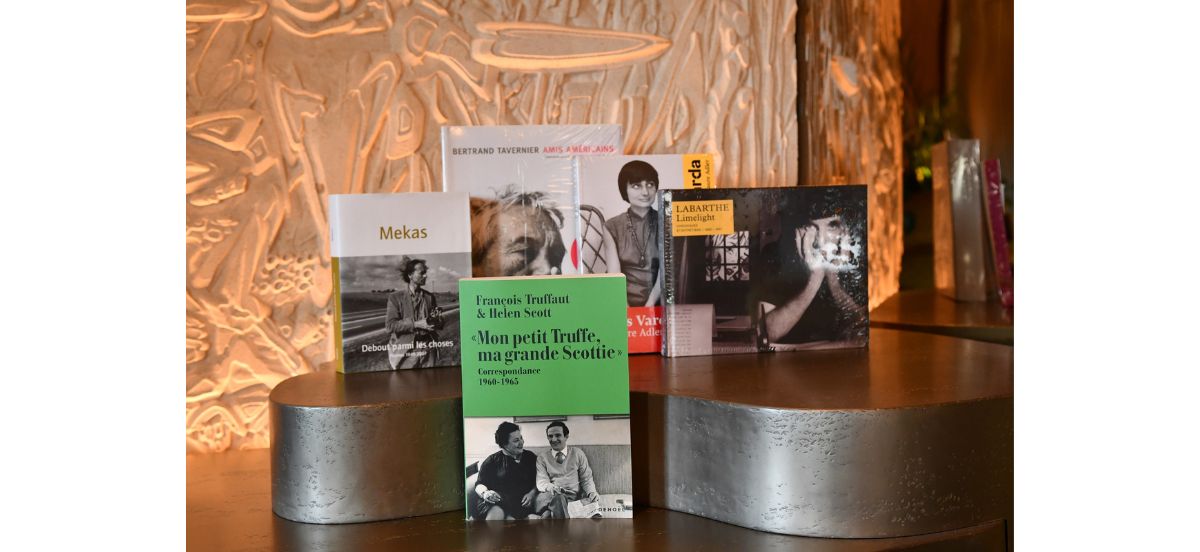

Nothing embodies the spirit of the holidays like the movies. This year, we’ve selected a few books about the masters of the 7th Art. It’s time to (re)discover the American Friends of Bertrand Tavernier, the friendship of François Truffaut and Hélène Scott, the genius of André S. Labarthe and Serge Daney, or the against all tides opinions of Pauline Kael.

Reading List

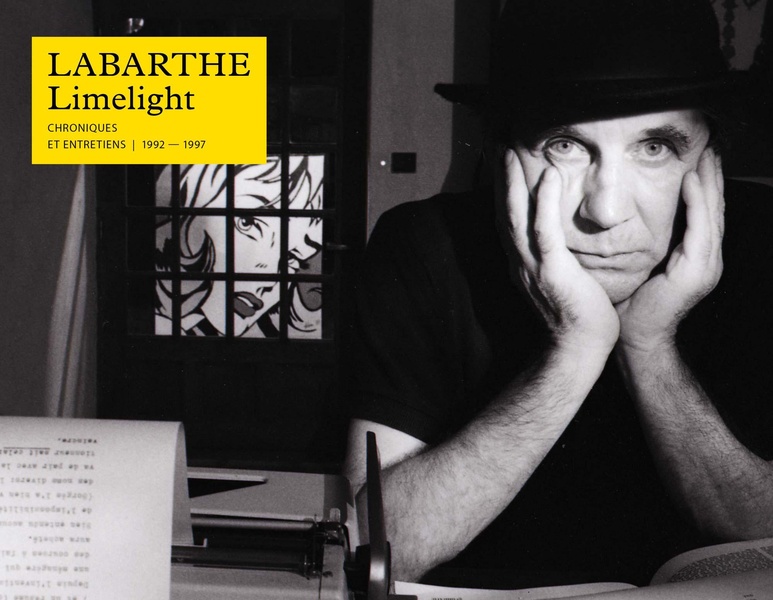

For several years, André S Labarthe contributed to the magazine Limelight a column that was part criticism, part diary, part ongoing correspondence. This was his first editorial collaboration, which he never missed. This first text deliberately touches on several fields: theater, photography, cinema, and fetishism. To make it clear that this column will not be devoted exclusively to cinema. An unusual chronicle of conversation, correspondence, notes and fragments, aphorisms and interviews.

What were Labarthe’s favorite subjects? The Lumière brothers, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Shirley Clarke, but also Georges Bataille, Roy Liechtenstein, Saul Steinberg… interviews with Jean-Luc Godard, Martin Scorsese, Joseph Losey, Alain Cuny… And finally, an interview with Paul Gégauff, a forgotten companion of the Nouvelle Vague.

Cahiers du Cinéma preferred to leave this interview – conducted in 67/68 by Labarthe, Jean Eustache and Bernadette Lafont – in the drawers, to avoid getting into trouble. It’s easy to see why, when you read the hilarious interview: it reveals a juicy little story, not very respectful of the Nouvelle Vague.

Labarthe Limelight, Chroniques et Entretiens, 1992-1997

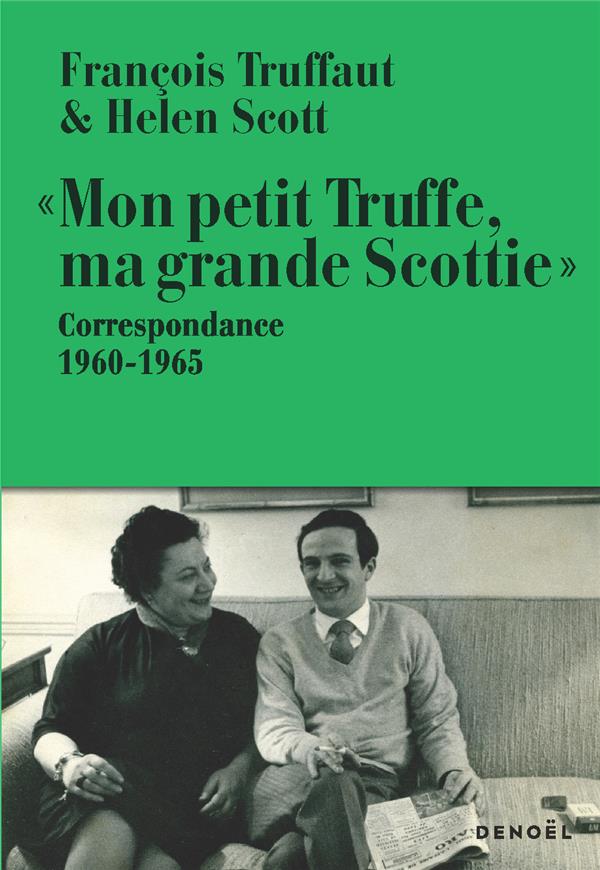

Helen Scott and François Truffaut met in New York in January 1960, when the young filmmaker was on his way there, buoyed by the success of his first film, Les Quatre Cents Coups (400 Blows). As soon as she saw him disembarking from the plane, the influential press attaché fell in love at first sight. Between 1960 and 1965, when they wrote to each other the most, Scott lived in New York and devoted herself to promoting the New Wave and Truffaut’s work in the United States.

In this selection of previously unpublished letters, we follow the genesis of Jules et Jim, La Peau douce, and Fahrenheit 451, as well as the mythical book of interviews between Hitchcock and Truffaut, for which Helen Scott was the linchpin. In these witty exchanges, the intimate often prevails over the professional: Truffaut, a great letter-writer, confides in her about his loves and doubts, while Scott in turn pours out her heart to the man she considers a genius, her “Truffaut chéri”, her “Truffe”, her “beau gosse.”A precious testimony to French cinema across the Atlantic, this dazzling correspondence reads like a novel.

“Mon Petit Truffe, Ma Grande Scottie” Correspondance 1960-1965, François Truffaut, Helen Scott, Denoel

Click here to purchase this book with us.

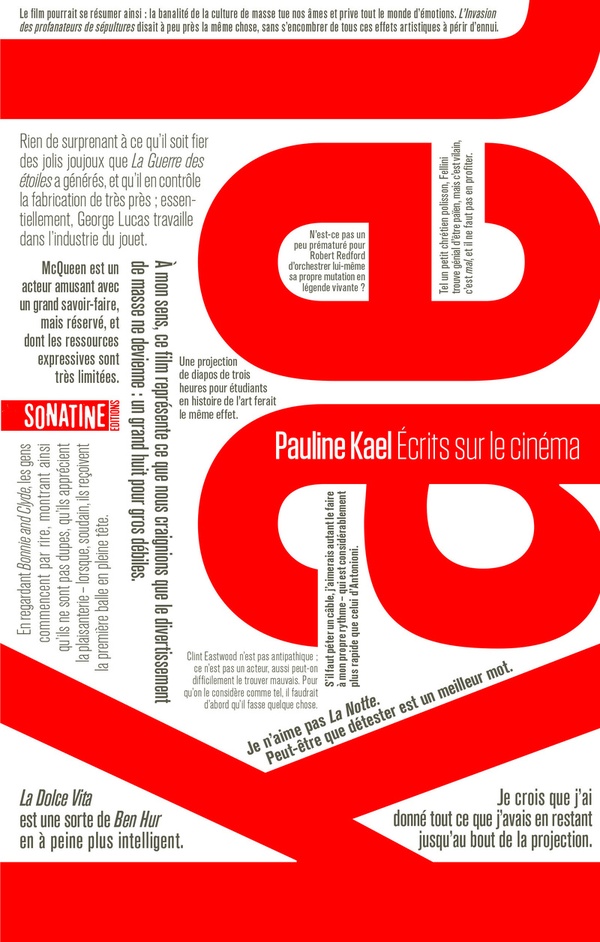

Pauline Kael is a name that has become emblematic of The New Yorker’s film column, and above all of an era that stretches from the late 60s to the very early 90s. Pauline Kael is above all a voice: direct, frank, conversational and irreverent. Her articles claim a freedom of tone and absolute subjectivity. But beyond these shocking formulas and other witticisms, this is the voice of a woman consumed by the arts and cinematic languages,

After seeing Werner Herzog’s Signs of Life, Kael comments « Si j’avais été une spectatrice occasionnelle, j’aurai pensé peut-être : quel ennui ! En tant que spectatrice assidue, j’ai pensé, J’espère que ce jeune homme inventera les techniques dont il a besoin, et que ce film constitue, en soi, un signe de vie. »

Reflecting on what ties us to movies and theather, she goes:

“A l’image de ces héros cyniques, qui étaient des idéalistes jusqu’à ce qu’ils découvrent que le monde est bien plus pourri que ce qu’on leur avait laissé croire, nous sommes tous des personnes déracinées, « loin de chez nous. » Et quand, découragés, nous aspirons à poser nos valises et à rentrer à la maison, avec tout ce que cela représente, ce chez nous n’existe plus. Mais il y a toujours les cinémas. Quelque soit la ville ou l’on se trouve, on peut toujours s’engouffrer dans une salle et retrouver sur l’écran le visages qui nous sont familiers —nos anciens « idéaux » qui comme nous ont vieilli et ne nous paraissent plus si idéaux que ça. Quoi de mieux pour attiser les flammes de notre masochisme qu’un bon navet dans un cinéma miteux, dans des villes qui se ressemblent toutes, avec les films et l’anonymat pour dénominateur commun ? Le cinéma, un art vénal et vulgaire pour un monde vénal et vulgaire — est au diapason de ce que nous ressentons.'”

What does Pauline Kael like? You’d be better off forgetting about finding out altogether. What matters is what she sees in a movie, and why. With that in mind, you’re in for a treat!

Ecrits sur le cinéma, by Pauline Kael, Sonatine

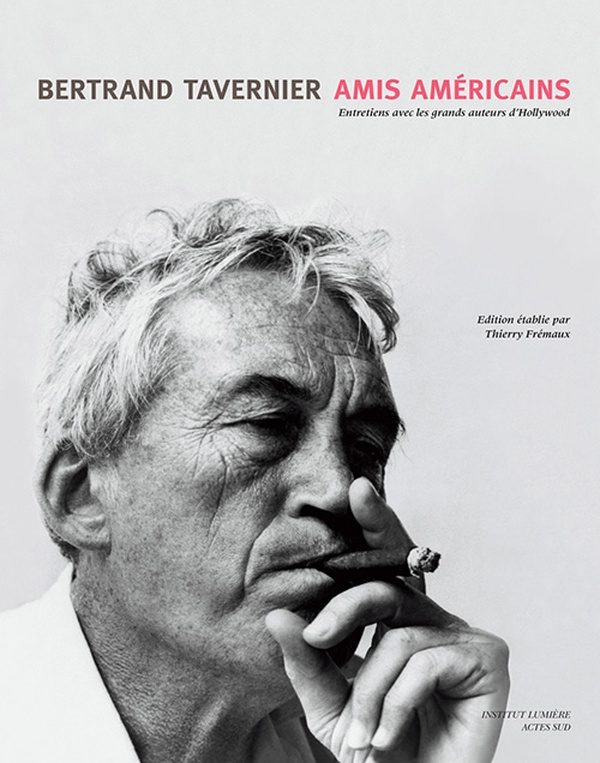

With over 400 photos, Amis Américains is a collection of interviews conducted by Bertrand Tavernier for various magazines, a logbook for the critic and press agent he once was. Fruitful exchanges with some of Hollywood’s greats: John Ford, for a last trip to Paris, William Wellman, Budd Boetticher, John Huston, Jacques Tourneur, John Berry, Elia Kazan, Robert Altman… but also abundant and fascinating dialogues with today’s great American filmmakers: Quentin Tarantino, Joe Dante, or Alexander Payne. Bertrand Tavernier passionately salutes twenty-eight auteurs who have left their mark on world cinema.

Reissued with new interviews in 2008, this book now appears in a new paperback edition, prefaced by a continuation of the interviews between Bertrand Tavernier and Thierry Frémaux, the book’s publisher.

A passionate exploration into the very heart of creation, but also a reflection of a way of experiencing cinephilia, Amis américains is a scrapbook that offers a meticulous, fragmented autopsy of American cinema from 1945 to the present day, and a review of Tavernier’s cinephile years.

Amis Américains by Bertrand Tavernier, Actes Sud

Click here to purchase this book with us.

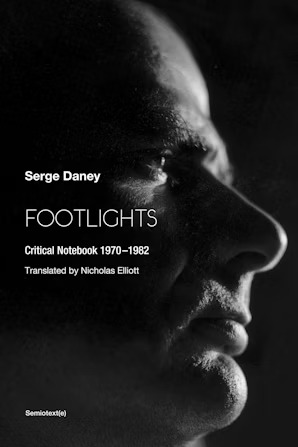

Footlights (1983) was the first book by Serge Daney, a film critic admired in his lifetime by Gilles Deleuze and Jean-Luc Godard and recognized since his premature death in 1992 as the most important French writer on film after André Bazin. Containing texts from the same period as the first volume of The Cinema House and the World, Footlights stands apart in Daney’s body of work as the only collection of his essays he conceived of as a book, organizing his seminal pieces from Cahiers du Cinéma by theme and linking them with original texts that reflect in a personal voice on the doubts, battles, and illuminations of a generation of film lovers inspired by the explorations of Lacanian theory and roused by the collective aspirations of Maoist dogma. In pieces on fellow travelers Godard and Straub-Huillet, on films ranging from Pasolini’s Salò to Spielberg’s Jaws, and on the difference between film language and television discourse, Daney offers the definitive portrait of an era of radical hope and disappointment.

Click here to purchase this book with us.