Our Favorite Fiction of 2024

As the year comes to a close, now is the time to look back at this year’s new fiction and select our favorites. Some won awards, some published to critical acclaim, all of them enchanted us and revived the magic of reading, and we hope they’ll speak to you too!

Reading List

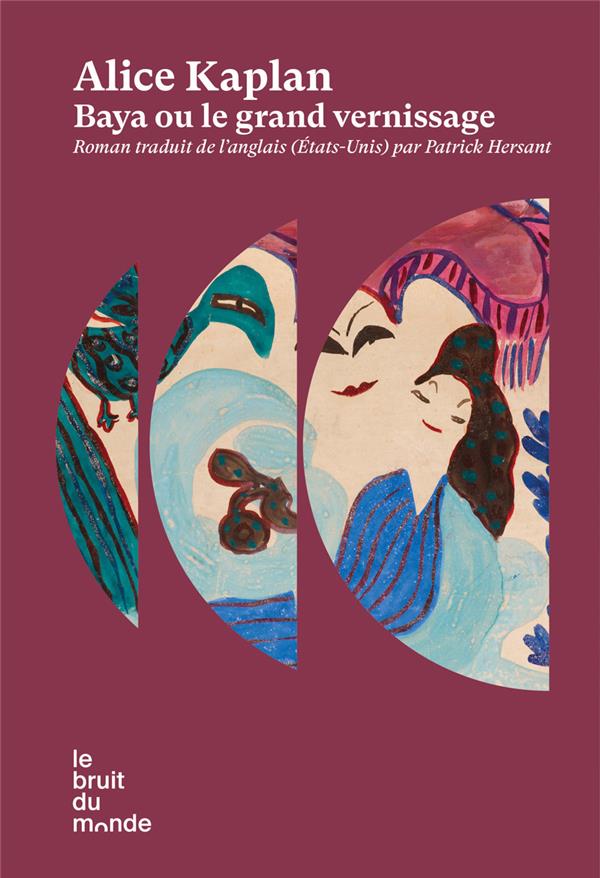

Alice Kaplan takes us on a journey of discovery of a little-known, self-effacing artist, thanks to her meticulous work in the archives, without concealing their limitations or her own questions. A fine connoisseur of Algeria, the professor of French literature at Yale University has written a book teeming with details in narrative fiction: “Baya takes me back to a time when, lightened by the burden of knowledge and the erosion caused by a lifetime of reflection, I looked at things more freely”.

Baya ou le grand vernissage, Alice Kaplan, traduit par Patrick Hersant, Le Bruit du monde.

Click here to purchase this book with us.

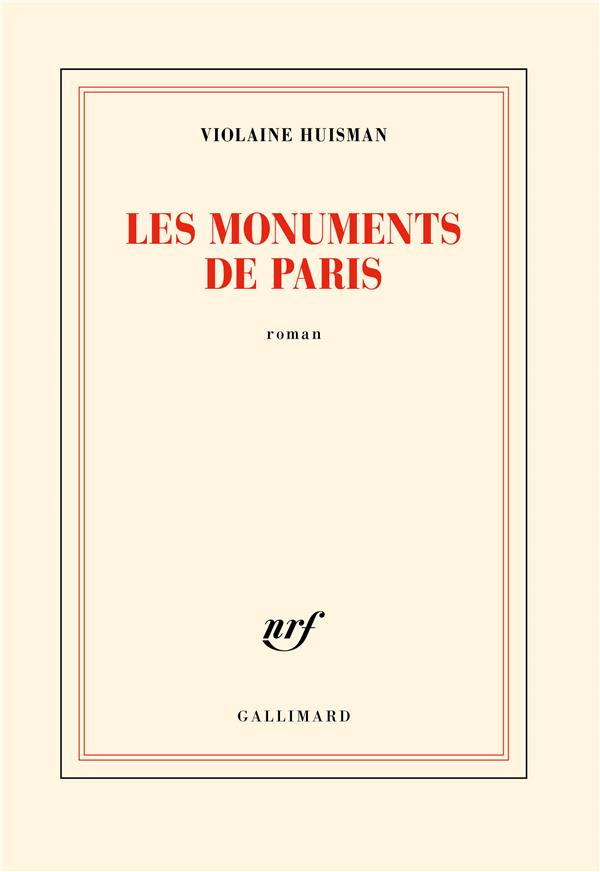

With the rigor, lucidity, and intelligence that she demonstrated in her previous books, Violaine delves into family and official archives to better make sense of her father, a man whom she described in his obituary as “an iconoclast, an unclassifiable, flamboyant, Balzacian character.” As Violaine digs into the past, a second figure emerges from her narrative, that of Denis’s father, Georges Huisman, historian, archivist, graduate of the prestigious Ecole Nationale des Chartes, senior civil servant, general secretary of L’Elysée, Director of Fine Arts under Prime Minister Jean Zay, and creator and founder of the Festival de Cannes.

This is a dark and sparkling novel, and one of the most interesting contemporary books I’ve read in recent years. Hadjimarkos Clarke is a translator and her feel for language is evident in the book. She is a masterful stylist and also a masterful storyteller – a rare combination. Like Gaspard Koenig, she flirts with offbeat humor, but similarly retains a capacity for sincerity and precision that is remarkable. This is also an ecological novel, although in a very different way than Humus. It almost feels fantastical, lush and horrifying and exploratory.

Read more

Click here to purchase this book with us.

Since the publication of Les Merveilles du Monde (POL, 2007), her debut novel, Célia Houdart has consistently enchanted us with short, breezy fiction. Underneath deceptively simple appearances, most of her novels have questioned the interconnectedness of fine arts, music and writing.

Les Fleurs sauvages, Houdart’s latest novel, might be another attempt at capturing the formative years of a visual artist. We follow the young Milva as she travels back and forth between two villages — La Chaux-de-Fonds (Swiss Jura), where her father owns a foundry, and Mane (Alps of Haute Provence), where her mother works as a taxi driver and lives with Milva’s (half-)brother, Theo, and his girlfriend, Kyoko. Milva draws everything that moves her, from the spectacular nature that surrounds her, to the scenes of the Japanese movies that fascinate her at the theater.

Click here to purchase this book with us.

Édouard Louis in Monique s’évade reveals his mom’s bravery. She is finally choosing herself and deciding that she does not deserve this. “This” is verbal abuse and daily insults flying out of her tormentor’s mouth once his whiskey drink is finished.

The author shows the reality of what it means to “escape” this life for a better one, yet an unknown one which can represent an insurmountable journey for the thousands of people who suffer this violence.

Louis will accompany her in this process, taking care of her even while he’s physically distant. At the end, he will finally get closer and repair some past wounds.

More than an escape and freedom story, this is a glimpse of the practical social, logistical, and economic realities which constrain or even make escape unthinkable for many depending on the individual’s situation.

An optimistic and heartwarming book, full of hope.

Monique s’évade by Édouard Louis, Cadre Rouge, SeuilClick here to purchase this book with us.

Prix Médicis (Fiction)

Born in Manchester, Ann’s story reflects the rise of the middle class thanks to industrial growth which followed the end of WWII. Underneath the tale of a gifted child who loves to learn, the chronicle of a young woman’s emancipation in the 60s and the 70s, followed by the slow dissolution of her marriage, Julia digs underground galleries in pursuit of the truth as others would search for a subtext. She feeds her search with the memories of others, with her mother’s diaries and her favorite novels. But the mystery surrounding her mother resists the vast amount of information she gathers:

“Enfant, je m’expliquai l’étrangeté de ma mère par la confusion du français, le fait qu’Ann était étrangère. Le passage à l’anglais quand j’avais 16 ans ne nous a pas rapprochées. Ma mère vient de l’extérieur, étrangère à sa fille, à son mari, à ses amis, à la famille d’Angleterre. En dépit de toutes les informations que je dispose, elle reste la personne la plus opaque que je connaisse.”

[“As a child, I explained my mother’s strangeness by the confusion of French, the fact that Ann was a foreigner. Switching to English when I was 16 didn’t bring us any closer. My mother was an outsider, a stranger to her daughter, her husband, her friends, her family in England. Despite all the information I have, she remains the less readable person I know.”]

Read more.

Click here to purchase this book with us.

This is a spare and gorgeous meditation on Gaudy’s father, on family and memory, and on the landscapes that are intertwined with our identities. Gaudy retraces her father’s steps from an island in Louisiana that shares his first name, to Algeria, to France. “Every family is an island,” she writes halfway through the book, “an ecosystem, enriched or disturbed by invasive species, an island whose roots nestle deep in the water. If you put your hand into the water at its surface, it forms backwash, concentric circles. If you do not lack energy and patience, the wave transforms little by little into darker layers, and the ones that seemed to have hardened like blocks of amber show signs of the movement which perturbs them – always acting, deep underneath our feet.”

She slowly teases out the portrait of her father. He appears in anecdotes, details, in his tendency towards hoarding, and his own art. It reminded me in that sense of Liliana’s Invincible Summer by Cristina Rivera Garza. Both books are invested in reconstructing the story of a person, of what their life was, of what it could have been. Her father tells her when he is alive that he has no memories of his own childhood. They have all been suppressed. Gaudy plunges into the void. Her grandfather fought in the French Resistance, her father arrived in Algeria as a young teacher in 1961. Personal histories emerge uneasily from geopolitical earthquakes.

Archipels is shot through with sadness, but above all it is intimate and lyrical. It summons poetry from ordinary landscapes or familial moments. It does feel like the description of an ecosystem in the end, one where each tremor or incursion becomes a breach, one that echoes across generations.

“La célébrité est ma vie. Celle que je savais que j’aurais, celle que j’ai fait en sorte d’avoir. Est-ce que j’étais préparée à un tel succès? Bien sûr que oui.”

[Fame is my life. The thing I knew I would have and did everything to have. Was I prepared for this kind of success? Yes, of course.]

We’ve all imagined what our lives might be like if we became famous. A superstar, a politician, a best-selling author, a professional soccer player… And all that glittering life implies. A private chauffeur, a big mansion, the adoration of the public, money, lots of money and therefore happiness, right? What a joy not to worry about the price of a Coke when you’re ordering in front of all your friends, isn’t it?

For most of us, this life is a well-nourished fantasy in our brains, and will never see the light of day. In fact, only 0.0086% of the world’s population is famous. But for those 0.0086%, the dream has become reality. By chance? Thanks to renowned parents? Or hard work, relentless dedication to reach the top.

In Maud Ventura’s second book, Célèbre, we follow a young girl named Cléo Louvent through the process of becoming the world’s biggest pop star of her generation.

Read more.

Click here to purchase this book with us

Le nord de l’Italie, début des années 80, un père vient chercher sa fille à l’école. Ils doivent retrouver la mère et la soeur pour déjeuner en famille au restaurant. C’était le plan, ou tout du moins, ce que le père affirme. Mais la mère et la soeur ne viendront pas, et le tête à tête se transforme en une cavale et dure deux années.

Click here to publish this book with us

Some books manage to capture turning points in life, periods of transition that we dread, that we try to put off until later, as long as possible, until they inevitably come crashing down on us, with lightning-fast violence. Nous n’étions pas des tendres is such a book. Sylvie Gracia depicts sensations up close: beauty, ugliness, sadness, bursts of pleasure, the chaos of existence as we blindly and tenaciously go through it.

Read more.

Nous n’étions pas des tendres by Sylvie Gracia, éd L’Iconoclaste.

Click here to purchase this book with us.